Communication, whether public or private, plays an important role in creating stigma (Escandon, 2024). In particular, media and social media strongly influence community beliefs, knowledge and attitudes about mental health problems, suicide, and alcohol and other drug (AOD) use (Ross et al., 2019). In fact, language is a matter of life and death; depictions of suicide in media and social media may increase the risk of subsequent suicidal behavior and death (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2020).

Although there is a lot of evidence that language is important, there is still no clear agreement about what terms we should use. For example, In a 2020 blog post by Huggett The researchers found that when people who had experienced suicide were surveyed, their views on the phrase were surprisingly mixed. 'committed suicide' – a phrase often regarded as outdated and derogatory. In addition, although there are few guidelines on how to talk about mental health in public spaces such as the media (e.g. Mindframe guidelines) or on social media (eg #chatsafe – see Catchpole, 2020), there is little advice on what language to use in private conversations to help reduce stigma.

This was therefore the aim of a recent Australian study by Elizabeth Paton and colleagues (2024) from Everymind in Australia. “To develop evidence-informed guidelines for national audiences, in addition to mass media and public communicators, on how language choice in personal or public communication can be used to reduce stigma, connect communities, reduce harm, and encourage help-seeking and offering behavior emphasizes.”

Language is important when it comes to mental health, so what language should we use to reduce stigma?

Methods

A mixed methods approach was used that included i) focus groups, ii) delphi consensus survey and iii) evaluation survey. The project was created by experienced people.

Focus groups conducted with professional communicators, people with professional or personal experience of mental health problems and people who identify or work with priority populations (eg young people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people). A total of 49 Australian adults participated in the focus group. Focus groups were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Themes generated from the focus groups were then used to develop a survey to be used in a Delphi technique. Participants (Australian adults with either professional experience in the media or other communication roles, OR professional experience in the mental health sector, or personal experience of mental health problems) were asked to rank a number of statements in order of importance for inclusion in a set of guidelines. . A second survey was completed to re-score items that either did not reach consensus or where open-ended responses indicated some confusion about the item.

The guidelines were launched via webinar in April 2023 and 60 participants completed the survey. to evaluate the adoption, use, usefulness and distribution of the guidelines. Website analytics are also collected to monitor downloads.

Results

Focus groups

The participants watched story and narrative are inseparable from word or image choices, although it was acknowledged that words can help transform the story into more hopeful, recovery-oriented narratives. Participants felt that there was no “one size fits all” approach to safe, inclusive representations and better representation of diverse populations in public narratives. The participants felt it the language must be adapted in each context and informed by those affected so as not to make assumptions. Language that moved away from clinical labels and focused more on health and well-being was preferred. Participants wanted more balanced, strengths-based and hopeful public representations of mental health that reflect the unique, personal experiences of individuals.

A Delphi survey

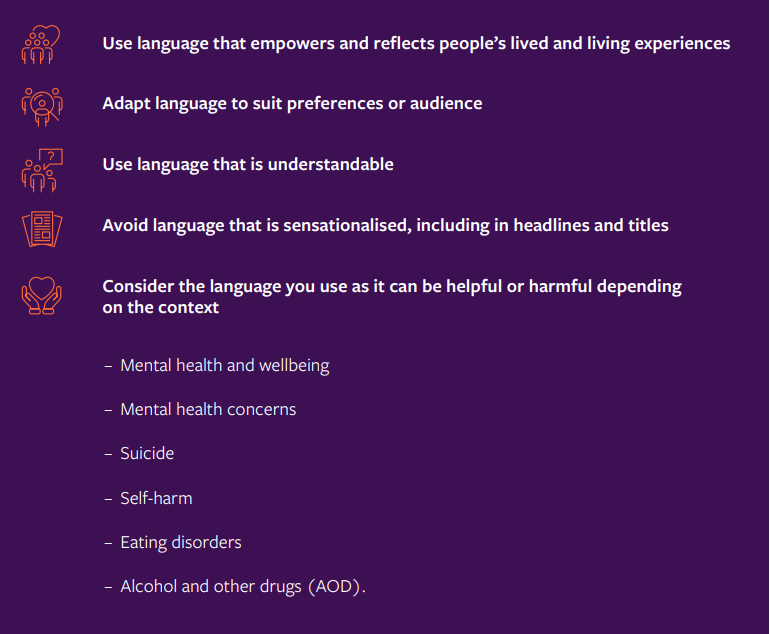

In both phases of the survey, a total of 36 (out of a possible 43) statements were reached and included in the development of the language guidelines. The main messages of the guidelines were:

- Use language that reinforces and reflects people's lived and life experiences

- Tailor language to preferences or audience

- Use understandable language

- Avoid sensational language, including headlines and headlines

- Be mindful of the language you use, as it can be helpful or harmful depending on the context.

Assessment

85 percent of participants watched or downloaded Our Words Matter resources since the start event. Participants mainly worked in clinical settings and used resources for training and facilitation. About two-thirds of respondents recommended or shared resources, primarily with other service providers. Almost all respondents (97.3%) agreed that the language guides were useful and indicated that they would continue to use them. 'language card: suicide' received the most downloads (297 downloads), followed by 'language card: mental health issues' (230 downloads) and 'quick reference guide: service providers (183 downloads). The instructions themselves During the evaluation period, it was downloaded 59 times and read 1,284 times via Issuu (a digital reader platform hosted on the site).

There is no 'one size fits all' approach to safe and inclusive language; We need representations that accurately reflect the individual and unique experience of mental health, suicide, and alcohol and other drug use.

Results

The authors conclude that:

At the start of the project, the researchers identified a gap in existing guidelines, policy, and literature to support communication about mental health issues, suicide, and AOD (alcohol and other drug) use. This gap in the evidence can contribute to inaccurate, misleading, and stigmatized language that is counterproductive to the identification, prevention, treatment, and recovery of mental illness, suicidality distress, suicidality, and AOD use problems in people's lives. .

This research fills an important gap that will contribute to reducing inaccurate, misleading, and stigmatized language.

Strengths and limitations

The authors are to be commended for including practice researchers in this project, particularly when seeking feedback on the direction of the project; A phase of the study period that rarely involves those with lived experience. The mixed-methods approach used in this study helps capture both nuance and broad, high-level insights—both of which are needed to inform policy. It was also nice to see a real-world lens applied to this research – evaluating how the guidelines were actually used in the “real world” was a great addition to the more scientific development of the guidelines.

For me, the main limitation of this study is its scope. The authors claim that they intend to in the introduction “Develop evidence-informed guidelines for national audiences, in addition to mass media and public communicators, that highlight how language choice in personal or public communication can be used to reduce stigma, connect communities, reduce harm, and encourage help-seeking and offering behavior “. I am not sure if the perspectives of 45 predominantly white Australian women and an additional 30-60 survey respondents (without specifying demographics or exact numbers) are sufficient to account for the broad scope of this work, particularly the national audience and the three. huge areas it aims to cover: mental health, suicide, alcohol and other drugs (AOD). The sample does not appear to be sufficient in size or diversity to make inferences and conclusions about language for the 26.6 million people living in Australia today. In the discussion section, the authors talk about the gaps in the literature that this study fills, but do not describe any systematic approach to the literature search to begin with. I wonder if there is merit in such an activity, which might have added weight to the focus group findings and provided a broader set of statements to use in the Delphi process.

The aim of this study was to bridge the gap between research and practice, providing real-world evaluation of guidelines.

Implications for practice

I feel we are running before we can walk by developing these guidelines. The question of what language should and shouldn't be used to discuss mental health is a question that needs to be answered definitively, and I think more work is needed here before we try to integrate it into guidelines. As indicated above, a systematic review together with a wider range of qualitative work would be useful here. a broader prioritization exercise using an approach such as of the James Lind Alliance would be helpful in this regard as well.

Once we have a better understanding of the language considered acceptable and appropriate by those with lived experience, it is vital to continue working with those with mental health experience to work out the best and most sensitive way to disseminate this guidance. . As someone with experience of mental illness myself, I appreciate the attention to language used. However, I sometimes worry that by placing too many rules and restrictions on language, we risk undoing the progress we've made in encouraging people to talk openly and honestly about their mental health experiences. It is important to me that any language guidelines do not inculcate a judgmental or punitive approach to errors, but rather aim to educate and inform the public. why certain language may be considered stigmatizing.

Are we trying to run before we can walk? More work needs to be done to understand what language is acceptable for those with mental health, suicide, alcohol and other drug use experiences.

Statement of interest

Undisclosed.

Connections

Primary paper

Paton, E., Jones, EP, Peprah, J., & Benson, M. (2024). Our Words Matter: Finding Consensus on Evolutionary and Private Language Around Suicide, Mental Health Concerns, and Alcohol and Other Drug Use. Media International Australia1329878X241278005.

Other references

Catchpole, Z. #chatsafe: helping young people communicate safely online about suicide. Mental Elf, May 2020.

Escandón, K. (2024). Towards non-stigmatizing media and language in mental health: addressing the social stigma of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 264491-493.

Huggett, J. The question of language: how should we talk about suicide? Mental Elf, August 2020.

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Braun, M., Pirkis, J., Till, B., Stack, S., Signor, M., … & Spittal, MJ (2020). The relationship between suicide in the media and suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj, 368.

Ross, AM, Morgan, AJ, Jorm, AF, & Reavley, NJ (2019). A systematic review of the impact of media reporting on serious mental illness on stigma and discrimination and interventions aimed at reducing any negative impacts. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 5411-31.