(Bloomberg) — Ivan Boesky, who rose to fame and fortune as a top Wall Street arbitrageur in the 1980s only to be exposed as a fraud in the era-defining insider trading scandal, has died. He was 87 years old.

The New York Times reported his death, citing his daughter, Marianne Boesky. No details were immediately available.

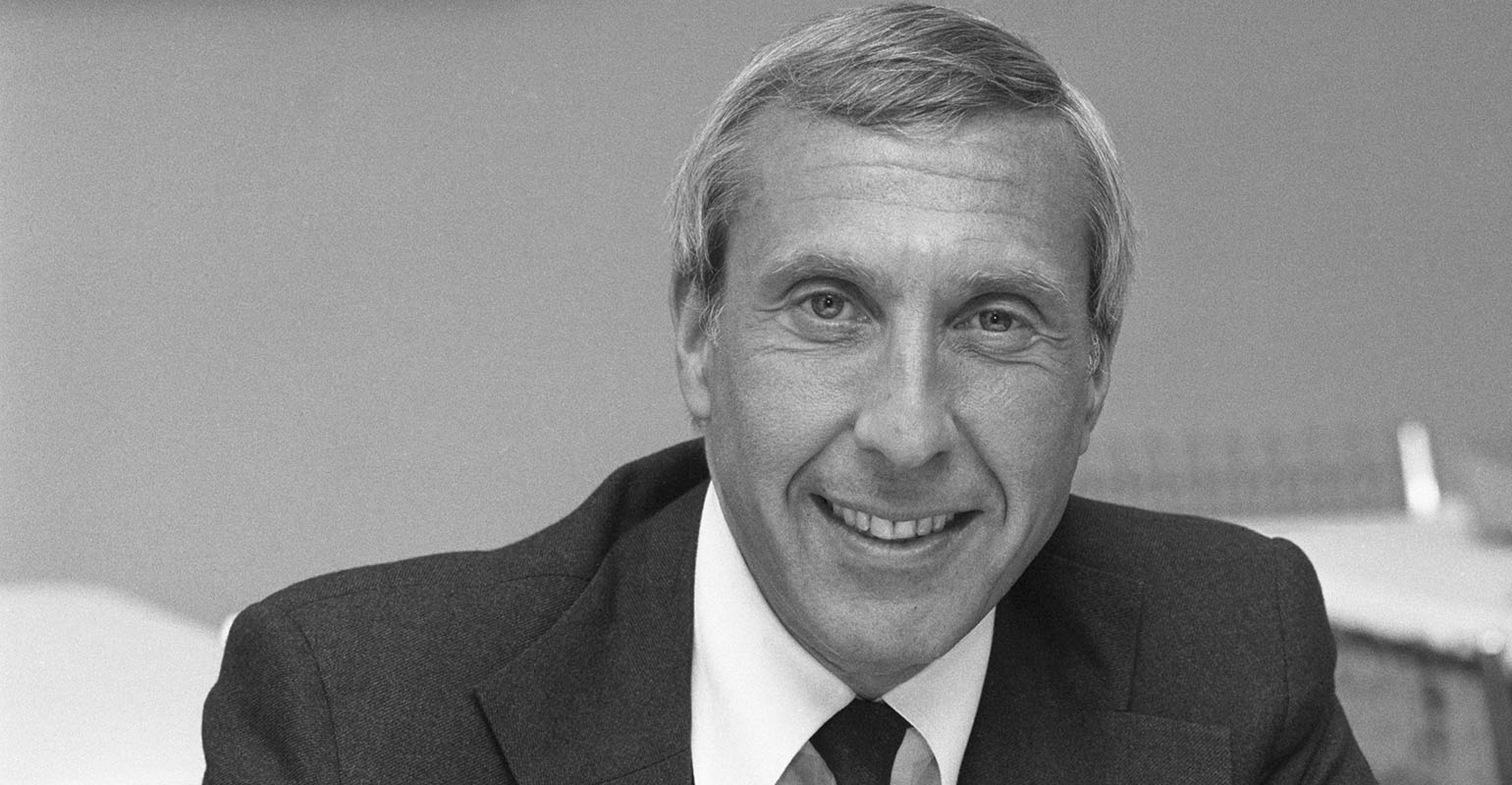

As junk bonds fueled a wave of hostile takeovers, Boesky became the archetype of the savvy speculator, reaping hundreds of millions of dollars in profits from buying bets. Then, after admitting to insider trading, Boesky became the poster child for Wall Street greed, his elongated face and toothy grin on the cover of Time magazine under the headline, “Ivan the Terrible.” He spent two years in prison.

Boesky's case sent shockwaves not just on Wall Street but across the US, confirming some investors' worst fears about the way capital markets worked. He was believed to have been the model for the character of Gordon Gekko, the violent villain played by Michael Douglas in the 1987 film. Wall Street. Gekko's speech in the film, declaring that “greed is good,” echoed Boesky's own assessment.

“Greed is OK, by the way,” Boesky told graduates of the University of California, Berkeley's business school in 1986, months before his downfall. “I want you to know this. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and feel good about yourself.”

Michigan bars

Ivan Frederick Boesky was born on March 6, 1937, in Detroit, the second child of William and Helen Boesky. His father ran a chain of local pubs called the Brass Rail.

At age 12, Boesky attended Cranbrook, a prestigious private academy in Bloomfield Hills, a suburb of Detroit, where he became a wrestling fanatic and received a “wrestler of the year” trophy. Despite his athletic success, he abruptly left Cranbrook before graduating and transferred to a public school.

Boesky attended Wayne State University in Detroit, the University of Michigan and Eastern Michigan University. He didn't graduate, but attended Detroit College of Law, earning a degree in 1964.

At the time, Boesky was married to Seema Silberstein, the daughter of Detroit real estate developer Ben Silberstein, whose properties included the Beverly Hills Hotel. He worked for a federal judge in Detroit, a relative of Silberstein, but was unable to land a job at one of the city's top law firms.

After his father's death in 1964, Boesky took over the last remaining Brass Rail bar, which by then featured topless dancers, and named it Le Club a-Go-Go, according to a 1993 Vanity Fair article. Two years later it went bankrupt and Boesky moved to New York, where he began a new career on Wall Street.

After several years working at financial firms where he learned the business of risk arbitrage, Boesky started his own investment fund in 1975 with $700,000 from his in-laws.

After six years of betting on the stocks of companies that were in play, he formed a new fund, just in time for a wave of acquisitions that changed the landscape of corporate America.

In 1984, Boesky made more than $100 million from the acquisition by Texaco Inc. of Getty Oil Co. and Chevron Corp. buying Gulf Oil Co., according to a 1984 Atlantic magazine story. The following year, he made about $50 million when Philip Morris Cos. bought General Foods Corp.

Unlike other umpires who generally avoided publicity, Boesky embraced it. He hired a publicist to quote him in the media, wrote a 1985 book about his experiences in high finance called “Merger Mania,” and traveled the country promoting it in speeches.

The SEC probe

By the mid-1980s, the Wall Street bull market that allowed savvy investors to make millions also led regulators to suspect that the markets were rigged in favor of insiders.

The Securities and Exchange Commission in mid-1985 opened an investigation into questionable trading by two Venezuela-based employees of Merrill Lynch & Co. that led them down a tangled path to the Wall Street fraud that ensnared Dennis Levine, an investment banker at Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc.

A year later, in June 1986, shortly after being arrested for insider trading, Levine pleaded guilty and agreed to cooperate with Manhattan US Attorney Rudy Giuliani. Levine told federal prosecutors that he had provided Boesky with nonpublic information about potential deals. Accused of making about $12 million from the illegal trades, Levine was later CONVICTED up to two years in prison.

A few months later, Boesky made a deal with the government. He would plead guilty to a felony count of conspiracy to file false trade records, i pay $100 million in fines and cooperation with federal authorities.

As part of the deal, Boesky secretly recorded his conversations with traders to help the government build its case against other Wall Street figures. The most prominent of these was Michael Milken, Drexel Burnhan's head of high-yield bond trading, who helped finance many of the era's corporate buyouts. Milken, who served nearly two years in prison for violating securities laws, was sorry in 2020 by then-President Donald Trump.

Boesky faced a maximum of five years in prison, but based on his cooperation with authorities, he was sentenced to three years. In April 1990, after suffering for about two years, he was released.

In a letter to a federal judge supporting the reduced sentence, prosecutors credited the financier with helping them understand the scale of Wall Street abuses: “What Boesky has given the government is a window into the rampant criminal behavior that has permeated the industry of securities in the 1980s, to an extent unknown to this office before Boesky began the collaboration.”

Unlike Milken, who spent most of his post-prison life engaging in philanthropy, Boesky largely disappeared from the public eye after his release. In 1991, Seema Boesky filed for divorce, which was finalized two years later. The couple had four children: William, Marianne, Theodore and John. He then lived with his second wife, Anna.